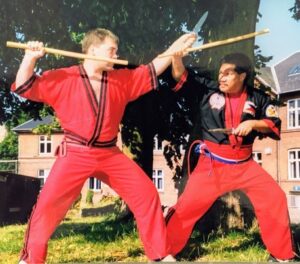

No matter what object Thorbjørn Hartelius holds, he can quickly turn them into a weapon to subdue an opponent. He can roll a newspaper into a blunt stick or make a dagger out of a fork. He can even form a whip using his jacket.

Hartelius has mastered arnis, a Filipino martial art form that mainly uses sticks and bladed weapons, but hardly uses it for fighting. Instead, he sees it as a way of living, a “glue that holds my life together”.

As the only arnis grandmaster in Denmark, Hartelius promotes this fighting style not just for its self-defense component but also for its rich heritage that allows different cultures to stick together.

A CHANCE ENCOUNTER

“I have to do this”

It was 39 years ago when the then-teenage Hartelius chanced upon a feature story about arnis on local television in northern Alberta in Canada. At the time, Toby, as he was called, had been exploring the province as an exchange student and had just visited a community of Filipinos who mainly worked in the Athabasca oil sands. The TV feature captured how arnis combined fighting using sticks, Filipino culture, and finesse, completely engrossing the teenager who thought, “I have to learn this.”

Toby visited the club the following day and met a local grandmaster who taught him the basics of arnis. As the teenager progressed from training, he realized that this fighting style gave him so much more than just learning self-defense.

“It gave me self-confidence and calmness,” Hartelius says about his feeling at the time. “I didn’t have to go out to prove myself or pick fights to be tough. Being with friends [and with other trainees and instructors] and becoming part of a fellowship in a community inside the dojo not only helped me a lot; we had had so much fun time together.”

Arnis gave me self-confidence and calmness. I didn’t have to go out to prove myself or pick fights to be tough.

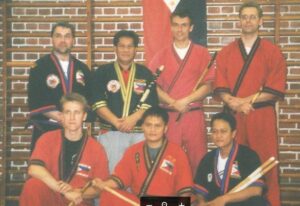

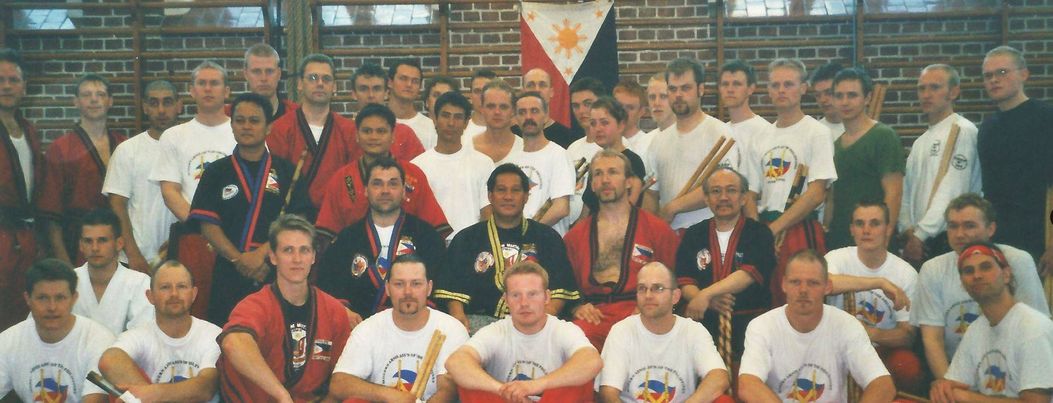

Hartelius has since trained with grandmasters and visited the Philippines several times to understand the culture behind this fighting style. In 2008—or 25 years since entering the dojo as a white-belt baguhan (Filipino for “novice”)—he became a Dakilang Lakan or the highest-ranked black belt arnis grandmaster.

It still amazes him up to this day how such a martial art form that traces its origins from ancient warfare in the pre-colonial Philippines can be a source of inner peace. Since modern arnis is considered a systematic form of self-defense with a focus on using sticks and blunt items, knives and other edged and bladed objects, and even improvised weapons, a practitioner needs strong awareness and self-control to employ these materials properly to subdue an opponent. Arnis trainees advance to mano-mano, or an empty-hand style, only after mastering the stick and knife techniques. This martial art form can kill an opponent or unarmed individuals, making it more important for arnisero to restrain their skills.

“Most people who get into sports prioritize getting fit. But in arnis, you also consider the inside—your mentality—you’re focusing on observing yourself, listening to every part of your body,” he says. “Of course, you can translate that later on to fighting. When you know that you would be able to inflict physical damage to someone, you’ll also need to find peace within yourself to be able to stop yourself.”

This Filipino martial arts form has truly become a big part of Hartelius’s life that he considers it “the backbone to being a dad and a husband.” Hartelius says his entire family is involved in arnis in many ways. His wife, Merete, is fully supportive of his activities and seminars, while two out of their three children have been training arnis for some years. He also integrates arnis into his full-time profession as a public primary school teacher, since it can improve children’s body motor skills, which will be helpful to develop their eye-hand coordination and ability to read and write. More than that, arnis builds up self-confidence so young students can “learn to protect [themselves] … and [move on] from mistakes and failure.”

When you know that you would be able to inflict physical damage on someone, you’ll also need to find peace within yourself to be able to stop yourself.

STICKING TOGETHER

A cultural meeting

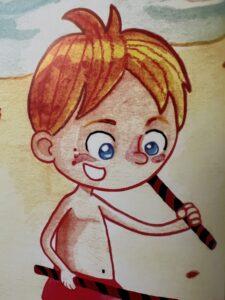

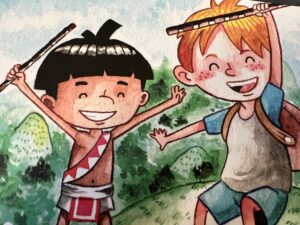

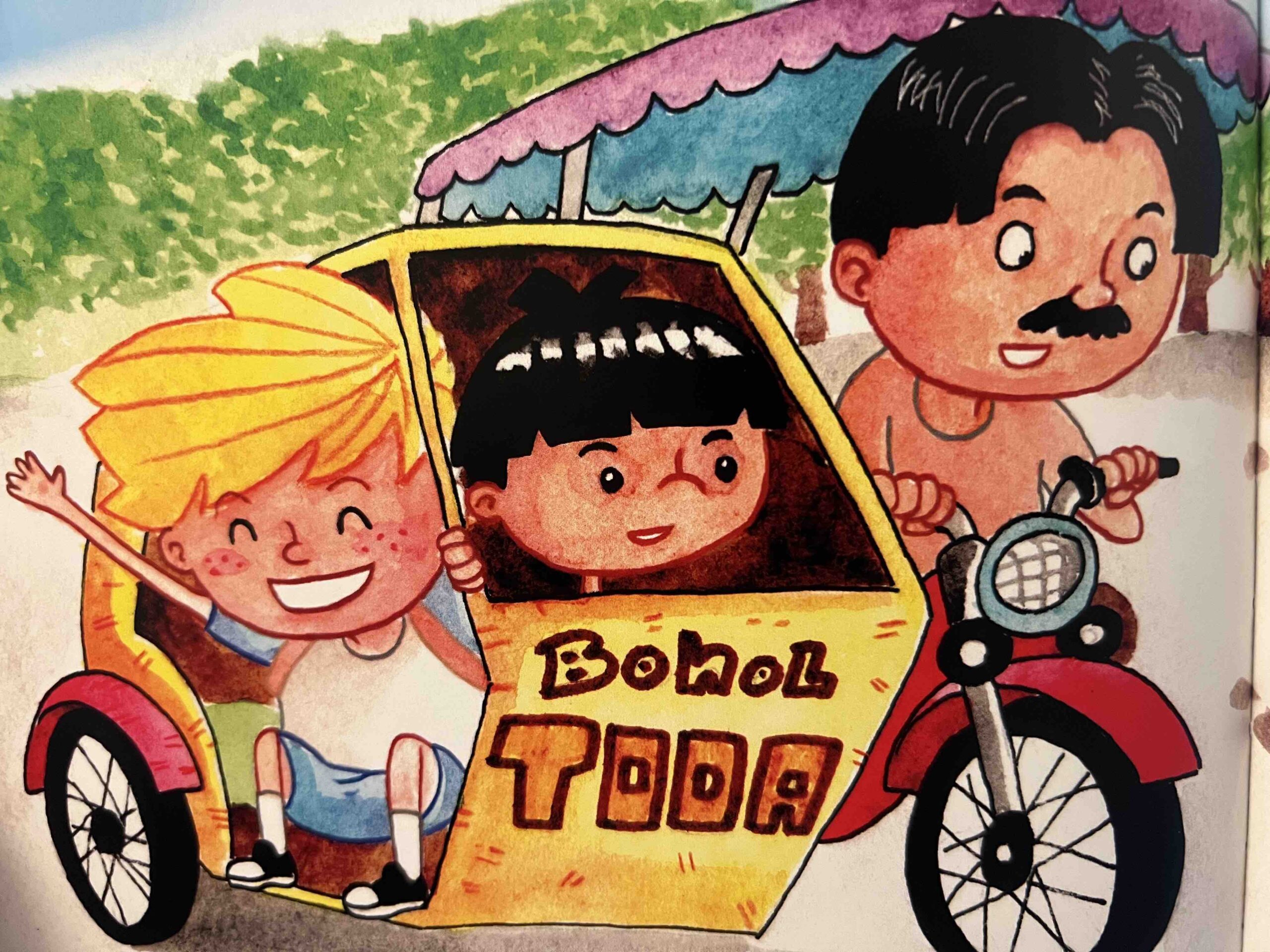

Crowds are flocking towards an open-air arena to cheer two boys engaged in a martial art exhibition. The clamor has attracted the attention of Martin and his father who are exploring a town center in Bohol. One of the fighters, Bayani, sends out quick thrusts and twirls of his rattan sticks, mesmerizing Martin who has never seen such an intriguing scene. After the exhibition, Bayani finds Martin lined up in front of a food stand and shares his snacks. The two boys quickly become good friends, with Bayani introducing arnis to Martin.

Hartelius remembers well how his first- and second-grade students reacted to Sticking Together, the picture book he read them sometime in September 2020: “They liked the story!”

Sticking Together is about two boys named Bayani and Martin who become friends because of arnis. In addition, Bayani introduces Martin to several aspects of Filipino culture, including bringing the young Dane to rice fields and showing him how a “boodle fight” or eating with bare hands with friends is done.

After so many years of thinking about a story that could capture his experience of arnis, Hartelius finally released Sticking Together in 2020 through his publication company Tiny Kingdom Press. Sticking Together seemed a fairy tale to many of Hartelius’s students: they were enchanted by its setting in the Philippines and amazed by Bayani’s appealing appearance as a young martial artist.

“For them, it was an ‘armchair travel’,” Hartelius adds, “because when they read and listen to the story, and in their minds, they can visit a place they have not been able to go to.”

More than introducing arnis and showing some places in the Philippines, the picture book also promotes diversity and understanding. Hartelius shares the book’s implicit topic of friendship is expressed through the “cultural meeting” between Bayani and Martin as a “way of seeing past the cultural differences” and allows the boys and book readers to “have fun and come, learn, and grow together.”

The “cultural meeting” between Bayani and Martin is a “way of seeing past the cultural differences”.

Sticking Together is the first in the six-book series titled Books That Stick with You planned by Hartelius. The second book will be set in Manila and focus on “family mentality in the Philippines”, a cultural aspect with which Hartelius resonates the most. For him, Danish society has changed so much in the past 50 years, and because of “many inputs from social media and the internet, so many young people like to be foreign than being Danish.” He hopes that the upcoming book and its theme can help Danish children understand the value of family.

Hartelius enlisted the help of Filipino illustrator Edralin Laurilla to design Sticking Together and dedicated EUR 1 (approximately PHP 58.00) of each copy sold to raise funds for the Philippine tarsier wildlife sanctuary. In addition, he collaborated with Handcrafters of Mary Enterprise (HOME), a community enterprise of artisan mothers in Cebu, Philippines, to create plush toys of Bayani and Martin made of recycled fabric.

“This is my way of giving back to the Philippines, a country that has given my family and me so much,” he says.

THE BIGGEST HOPE

Passing on the art

While arnis is less popular than other Asian martial art forms, Hartelius still welcomes the attention it has gotten recently, especially in films such as Dune (2021) and The Old Guard (2020). He hopes, though, that future productions can keep the focus on the art and culture behind this Filipino martial art form to pass on its heritage. It is also encouraging for him to think that more people who have watched films that feature arnis will want to “Google where this art form comes from”, and then “discover the Philippines, which has been overseen for quite some time.”

For him, however, there are “small signs” of growing interest in arnis, especially as Filipino federations and clubs champion the art as a viable competitive sport in regional games.

Most recently, the Filipino government hailed the inclusion of arnis in the program of the upcoming Southeast Asian Games in Cambodia in May 2023. “The biggest hope, of course, is to have it on the Olympic program,” he adds.

Next year, Hartelius will mark the 40th anniversary of his first foray into arnis. As long as that hope for arnis to receive worldwide renown remains, he will continue brandishing rattan sticks even after retirement. As the only arnis grandmaster in Denmark, Hartelius knows the great obligation his role has for him.

“I will keep teaching arnis, and hopefully, I can pass it on to as many people as I can, anywhere in this world,” he says.

Producer: Andy Peñafuerte III Photos courtesy of Thorbjørn Hartelius