From the rotating trays of the Chinese dinner table to the boodle fight tradition of military-style eating in the Philippines, and from using chopsticks with precision and dexterity in Japan to scooping food freely with bare hands in Malaysia, dining in Asia offers up a wide variety of cultural experiences that travelers often find fun or amusing.

Southeast Asians, arguably, are the most communal foodies on the continent and even a simple conversation with them can be a spontaneous dining invitation. Many styles of Southeast Asian cuisine encourage sharing since food is seen to create and maintain social relationships and sharing it with others is a tradition entrenched in occasions that can be spiritual or cultural in nature.

In the Philippines, a “communal mentality” or high dependency on each other is present especially in the rural agricultural regions where the concept of family and community is equal. Villagers often express this by “extending [their] home to the streets.” And so, a very common form of greeting people from the community is by asking “Kumain ka na ba?” (Have you eaten yet?), since many Filipinos regard sharing food as sharing their blessings. Food then functions beyond sustenance; it brings people with a lot of differences together and thus becomes a “social lubricant.” [xii]

Religious holidays abound in the Philippine calendar, due in large part to its Spanish colonial history. Numerous barangays (small villages) and bayans (towns) hold fiestas, called in Filipino as pista or kapistahan, mostly in honor of their Christian patron saints, or in celebration of their good harvest. Pistas are celebrated with massive feasts and banquets called salu-salo, a ubiquitous Philippine food sharing tradition often taking place among neighbors and guests. Families or communities prepare “special home-cooked ‘feast’ foods” that can range from lechon (roast pork), relleno (fish stuffed with fish meat mixed with vegetables), and tinolang manok (chicken boiled in ginger and chayote broth). At Christmas or family reunions, dishes such as hams or sausages, seen as rare or expensive especially when compared to local produce, are regarded as “special food” but nevertheless shared with guests.

Salu-salo in town festivals may be done in the boodle fight-style, where food is served on a long stretch of banana leaves in a trestle table. Diners practice kamayan or scooping food with bare hands while adopting the military style of eating while standing shoulder to shoulder on both sides of the table.

Another distinct feature of the food sharing culture in the Philippines is the use of sawsawan [xvii] or special condiments that function as marinades in many Filipino dishes; or dips that adjust or enhance the flavors of food in salu-salo tables; or sauces for street foods, fried nibbles, and merienda (afternoon snacks). Some of the many savory sawsawan present in the Filipino culinary lexicon are:

- Agre dulce or Filipino sweet and sour sauce, a mixture of cornstarch, salt, sugar, water, chili sauce, and vinegar;

- Atsara [xix] or a relish made of pickled grated unripe papaya, julienned carrots and ginger, onion, pepper, and garlic;

- Bagoong or fermented krill or fish, whose liquid by-product is called patis;

- Flavorful mixtures of vinegar and soy sauce sprinkled with crushed garlic, black pepper, and crushed chilis for grilled meat;

- Latik, which can be a caramelized coconut cream syrup for the Bisaya people or toasted coconut curds for the Tagalog people mainly used for suman or sticky rice cakes;

- Manong’s Sauce, a colloquial term for a sweet sauce made of brown sugar, soy sauce, and garlic, and is a dip for skewered fish balls usually sold by street food vendor;

- Palapa or a sweet and spicy dip made with thinly chopped white scallions, crushed ginger, turmeric, red chili pepper, and niyog (grated coconut);

- Toyomansi, a simple mixture of soy sauce, calamansi (Philippine lime), and siling labuyo (small red chili pepper)

In an essay for Philippine World-view, a book that articulates the concepts of the daily Filipino life, renowned Filipina food critic Doreen Fernandez says the sawsawan allows the consumer “to take part in the creation of the dish just as the cook has,” and that the basic Filipino cooking method “invites consumer participation.”[xxiii]

That, along with the kamayan and salu-salo traditions make the Philippine food sharing culture “interactive”, says US-based Filipino restaurateur Miguel Trinidad, one of the authors of I Am a Filipino: And This Is How We Cook cookbook, in an interview. He also explains that these traditions allow diners to interact with the food while catching up with their friends and family.

Fernandez explains why there is an underlying language in this culture:

If one’s presence, expected or not, does not occasion a fuss, but involves the use of the daily tableware and the customary fare, then [that person] is hindi ibang tao (one of us) and can share sawsawan and whatever food there is with the family.[xxv]

Some foreigners have related the Philippine food sharing culture to Filipinos’ hospitality and generosity. Philippine-based Canadian blogger Kyle Jennerman was so inspired by this generosity that he organized his own village fiesta in 2014. In a review, Jennerman says the locals he encountered in many Filipino villages told him they get “happiness and blessings” in return for the simple act of sharing food with strangers.

Polish-Australian food and beverage (F&B) industry consultant Peter Pysk notes in an article the influence of religion on the Filipino food culture, where the act of praying before eating “reminds people [of] the more important things in life.” Beyond this, however, Pysk argues that “there is a lack of care on daily meals” because of financial hardships people face. He also notes that Philippine food heritage is not primarily taught in school, so he suggests adding this to basic education, so to help Filipinos represent their food as a world cuisine beyond the usual adobo fare.

The Philippine cuisine is “a learned taste and a learned way of eating,” so don’t be confused if a Chinese-looking dish may taste everything but Chinese, or a Spanish-sounding food isn’t cooked the way Spaniards do. Philippine cuisine can hold up against the familiar tastes of Southeast Asian food, but ours is best served in the company of others in a salu-salo. And so, we ask you, “Kumain ka na ba?”

Works Cited

[i] Jr., S. D. (2012, June 10). The boodle fight. Retrieved September 2019, from The Philippine Daily Inquirer.

[ii] Pallardy, C. (2017, March 12). Dining etiquette in Asia: Everything you need to know. Retrieved September 2019, from Intrepid Travel.

[iii] Dunston, L. (2013, October 3). Asian Food Etiquette – Eating, Drinking and Dining Etiquette. Retrieved October 2019, from Grantourismo.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Esterik, P. V. (2008). Eating Out. In P. V. Esterik, Food Culture in Southeast Asia (p. 79). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Kleinfelder, P. (2004). American Influence on Filipino Food Culture – A Case Study. Munich: LMU Munich (Amerika Institut).

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Merano, V. (2011, July 24). 25 Filipino Recipes to Enjoy with the Family. Retrieved September 2019, from Panlasang Pinoy.

[xi] Pysk, P. (2018, June 7). Understanding Filipino food culture through the eyes of a foreigner. Retrieved September 2019, from F&B Report.

[xii] Fernandez, Doreen. (1986). Food and the Filipino. In V. Enriquez, Philippine World-View (pp. 20-45). Singapore: Southeast Asian Studies Program, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

[xiii] Escalona, K. (2017, August 26). 7 Unusual Filipino Practices Most Foreigners Won’t Understand. Retrieved September 2019, from The Culture Trip.

[xiv] Sim, D. (2018, September 25). Filipino Cooking and Culture. Retrieved September 2019, from The Spruce Eats.

[xv] Russell, S. (n.d.). Christianity in the Philippines. Retrieved September 2019, from Crossroads: An Introduction to Southeast Asia.

[xvi] Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (2003). Culture Ingested: On the Indigenization of Philippine Food. Gastronomica, 58-71.

[xvii] Fernandez, Doreen. (1986). Food and the Filipino

[xviii] Agre Dulce. (2010, March 14). Retrieved September 2019, from Lutong Cavite.

[xix] Zabilka, G. (2007). Chapter IX – Foods. In G. Zabilka, Customs and Culture of the Phillippines (p. 117). Tuttle Publishing.

[xx] Latik / Fried Coconut Milk Solids. (2006, August 5). Retrieved September 2019, from Market Manila.

[xxi] Ignacio, M. (2013, August 14). Fish Ball Sauce Recipe – Just Like Manong’s! Retrieved September 2019, from Certified Foodies.

[xxii] Morocco, C. (2017, July 26). This Condiment Is Sweet, Spicy, Garlicky and Just Ridiculously Good. Retrieved September 2019, from Healthyish.

[xxiii] Fernandez, Doreen. (1986).

[xxiv] Ting, J. (2018, December 4). The Cuisine of the Philippines Is More Diverse Than You Ever Imagined. Retrieved August 2019, from Saveur.

[xxv] Fernandez, Doreen. (1986).

[xxvi] Harvie, J. (2017, September 7). Let’s eat! Food and sharing in the Philippines. Retrieved September 2019, from Filipina Wives.

[xxvii] Jennerman, K. (2015, February 23). Four Filipino Cultural Traits That Inspire My Life. Retrieved September 2019, from #BecomingFilipino.

[xxviii] Pysk, P. (2018, June 7).

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Stuart, G. U. (n.d.). The ABCDE of Philippine Cuisine: A Culinary Opinion. Retrieved September 2019, from stuartxchange.

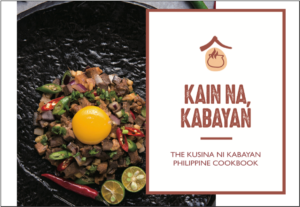

This article first appeared in the Kain na, Kabayan: The Kusina ni Kabayan Philippine Cookbook.

Email kusinanikabayan@gmail.com to get your copy.

Photos: Jonnalyn Shi, Gil Librado