The Philippines shares common dining traditions with its Southeast Asian neighbors: food is meant to be shared with everyone and many Philippine dishes reflect a rich blend of tastes influenced by the culinary cultures of China, Malay, India, Arabia, Spain, and America. Smithsonian magazine has even opined that “Filipino cuisine was Asian fusion before there was Asian fusion.”

Renowned Filipina food critic Doreen Fernandez notes the indigenization process in Philippine cuisine:

“The process seems to start with a foreign dish in its original form, brought in by foreigners. It is then taught to a native cook, who naturally adapts it to the tastes he knows and the ingredients he can get, thus both borrowing and adapting. Eventually, he improvises on it, thus creating a new dish that in time becomes so entrenched in the native cuisine and lifestyle that its origins are practically forgotten. That is indigenization, and in the Philippines, the process starts with a foreign element and ends with a dish that can truly be called part of Philippine cuisine.”

History and influences

Even before the Philippine colonization era that had begun in the early 15th century, ancestors of Filipinos had direct trade or barter with neighboring kingdoms and dynasties in China, India, Malaysia, Borneo, and Thailand, allowing an exchange of goods, products, and culture. This resulted in the introduction of new ingredients and foreign methods of cooking.

The Malay culinary style of using hot chilies and gata (coconut milk) in sauces to balance the level of spiciness is present in some dishes of the Bicolanos, or people of the southeastern region of Luzon island. Their laing dish is made of meat and shredded taro leaves cooked in thick gata and spiced with siling labuyo (red chili pepper)

The Chinese, mostly from the present-day Fujian and Guangzhou Provinces, arrived in the Philippines as early as 9th century. From the subsequent centuries of interaction from Chinese merchants and sojourners, ancient Filipinos acquired various Hokkien (Fujian) food products and names that have entered the Filipino culinary lexicon. Such examples are lumpia, a ready-to-eat meat-and-vegetable wrap dipped in vinegar that is regarded to have started Filipinos’ penchant for pairing food with sawsawan (dips); hopia or a sweet pastry made of beans and flour; and soybean products such as toyo (soy sauce) and tokwa (soy bean curds). Cantonese (Guangzhou) food such as siomai (dumplings) and siopao (steamed meat buns) also entered the Philippine cuisine and is now mostly eaten as merienda (afternoon snack). Pancit, a generic Filipino term for noodles, comes from China and has been acculturated in Philippine cuisine so much that it spawned many local variants with sabaw (broth) like La Paz Bachoy, or sarsa (thick sauce) such as pancit luglug from the Quezon Province.

Fernandez also notes that Chinese cuisine has been assimilated into lower- and middle-class Philippine cuisine, in the form of contemporary turu-turo (point-and-eat style, literally “point-point”) eateries and street snack stalls.

On the other hand, food critic Reynaldo Alejandro says in his groundbreaking culinary guide The Philippine Cookbook that the Spaniards, who had occupied the Philippines for 300 years starting from the 15th century, taught Filipinos the “gentle art” of sautéing with garlic, onions, tomatoes, and olive oil. Fernandez notes that the Spaniards exercised their influence on the Filipino illustrado (elite) class through Spanish-style food such as paella, rellenong manok (stuffed chicken), jamon (ham), and quezo de bola (large cheese ball) to name a few, which, at present, are considered as prestigious fiesta fare.

Two popular Filipino dishes that are derived from the Spanish cooking style are adobo and longganisa. Tagalog people, who mainly hail from the Central Luzon region, have various ways of cooking adobo, a stew made of soy sauce, vinegar, pepper, and meat so ubiquitous that it has been considered an identifying dish of Philippine cuisine. Ilocanos from the northern Philippines have the Vigan longganisa, a plump pork sausage with a strong kick of garlic and ground pepper named after the port town of Vigan, believed to have been the entry point of Spanish galleons.

Philippine cuisine also makes plentiful use of seafood, especially in the island provinces in the Visayas and Mindanao regions. Such a popular seafood dish is called kinilaw, or the Philippine ceviche, which emphasizes the juiciness of raw fish sliced thin and soaked in native vinegar with spices and onions. Fish mainly used for kinilaw is tuna or blue marlin.

The cuisine of the Moros, or the ethnic groups of Muslim Filipinos residing mostly in the southern region of Mindanao, has much in common with the rich and spicy cuisines from Arabia and India. Mindanaoan dishes are richly flavored with turmeric, coriander, lemongrass, cumin, chilies, and spices that are not commonly used in the other regions of the Philippines.

American colonizers entered the Philippines in the early 19th century and they introduced Western dishes such as hamburgers, fried chicken, soft drinks, and many types of fast foods, as well as technology such as the refrigerator and microwave ovens that facilitate cooking and food preservation. This would eventually develop Filipinos’ liking for such a quick service food style and transnational food companies such as McDonald’s and KFC are present almost everywhere in the country. Their predominant local competitor is Jollibee, which serves American-style hamburgers, fried chicken and sweet Pinoy-style spaghetti.

A common criticism of Philippine cuisine is it is too maalat (salty), matamis (sweet), or mataba (greasy), and it has a reputation of being unrefined and unimaginative compared to other popular Asian tastes. Many travelers have even called Philippine cuisine “the worst in Asia”, and that its lovers are only locals. But for travelers to fully enjoy the cuisine, they have to go beyond the fast-food chains and small-time turu-turo eateries, since the food that can satisfy the Western palate can mainly be found in the Bicol and Mindanao regions.

Fine-dining is still a foreign concept currently explored by many local restaurants in major cities. The Chinese, meanwhile, will find Filipino food familiar, through the many pancit products inspired by Fujian and Guangzhou cuisines.

Philippine cuisine is a “sum of its history”, says renowned food critic Michaela Fenix in the important guide, Kulinarya: A Guidebook to Philippine Cuisine. This cuisine will still evolve as many Filipinos find ways to incorporate delectable tastes from different world cuisines.

Works Cited

[i] Brent Roman; Susan Russell. (2009, November 16). Southeast Asian Food and Culture. Northern Illinois University Grade 9-12 (High School) Lesson Module. Illinois, United States: Northern Illinois University.

[ii] Fernandez, D. (1991). Beyond Sans Rival: Exploring the French Influence on Philippine Gastronomy. Philippine Studies, 104-112.

[iii] Sue Halpern; Bill McKibben. (2015, May). Filipino Cuisine Was Asian Fusion Before “Asian Fusion” Existed. Retrieved September 2019, from Smithsonian Magazine:

[iv] Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett; Doreen Fernandez. (2003). Culture Ingested: On the Indigenization of Philippine Food. Gastronomica, 58-71.

[v] Faustino, A. I. (n.d.). Spanish Influence on Filipino Food. Retrieved September 2019, from Filipino Kastila.

[vi] Fernandez, D. (1998). Philippine Food. Pahiyas: A Philippine Harvest, 51-52.

[vii] Esterik, P. V. (2008). Historical Overview. In P. V. Esterik, Food Culture in Southeast Asia (pp. 1-18). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group.

[viii] Ang See, C. (2011). Acculturation, Localization and Chinese Foodways in the Philippines. In Chinese Food and Foodways in Southeast Asia and Beyond (pp. 124-139). Singapore: NUS Press Singapore.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Fernandez, D. (1998).

[xiii] Fernandez, Doreen. (1986). Food and the Filipino. In V. Enriquez, Philippine World-View (pp. 20-45). Singapore: Southeast Asian Studies Program, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

[xiv] Alejandro, R. (1985). The Philippine Cookbook. New York: The Berkley Publishing Group.

[xv] Fernandez, Doreen. (1986).

[xvi] Esterik, P. V. (2008). Typical Meals. In P. V. Esterik, Food Culture in Southeast Asia (pp. 53-77). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group.

[xvii] Vigan Longganisa. (n.d.). Retrieved September 2019, from Vigan.ph:

[xviii] SEASite Project. (n.d.). Visayan Culinary Culture. Retrieved September 2019, from Tagalog.

[xix] Garcia Reyes, M. (2019, February 19). A Gastronomic Journey Through Southern Mindanao. Retrieved October 2019, from Philippine Tatler:

[xx] Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett; Doreen Fernandez. (2003).

[xxi] Fernandez, D. (1998).

[xxii] How other countries influence Filipino food. (2016, November 19). Retrieved September 2019, from FoodNet PH.

[xxiii] Influence of Other Countries to Philippine Cuisine. (2019, February 10). Retrieved September 2019, from Philippines Insider.

[xxiv] Kimani, R. (2016, October 28). 10 Interesting Facts You Need To Know About Food in The Philippines. Retrieved October 2019, from Authentic Foodquest.

[xxv] Fitzsimons, J. (2013, June 11). Food in the Philippines: A Lingering Taste of Salty Disappointment. Retrieved August 2019, from Indiana Jo.

[xxvi] Philippines in Detail: Eating. (n.d.). Retrieved October 2019, from The Lonely Planet.

[xxvii] Various public comments from the Indiana Jo blog.

[xxviii] Philippines in Detail: Eating. (n.d.).

[xxix] Pyne, I. (2019, March 25). Filipino fine dining: does it exist, and what is it? Retrieved October 2019, from South China Morning Post.

[xxx] Fenix, M. (2013). The Culinary History of the Philippines. In M. Fenix, & M. Besa Roxas (Eds.), Kulinarya: A Guidebook to Philippine Cuisine. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: The House Printers Corporation.

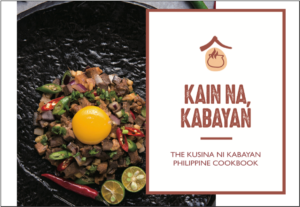

This article first appeared in the Kain na, Kabayan: The Kusina ni Kabayan Philippine Cookbook.

Email kusinanikabayan@gmail.com to get your copy.

Photos: Jensen Moreno, Perlita Pengson, Gil Librado